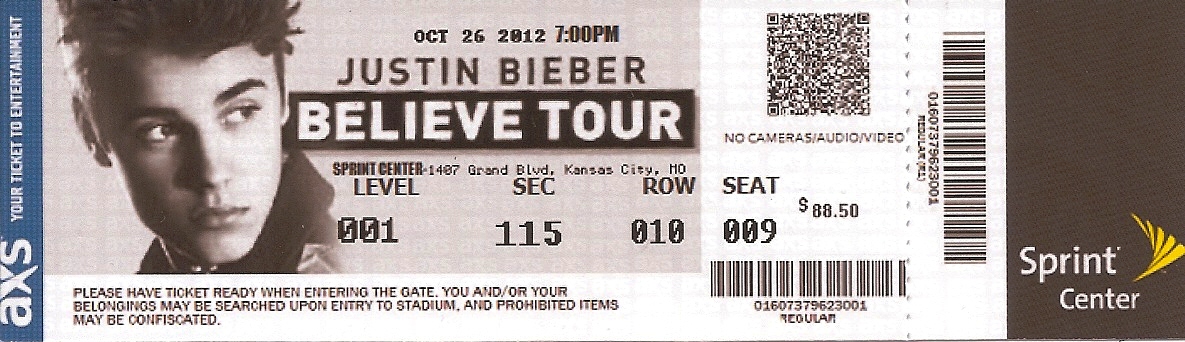

Are Justin Bieber tickets property?

The Wall Street Journal recently published an interesting article that considers whether concert tickets are property. The philosophical question has practical implications, as California lawmakers are considering whether to ban paperless tickets, which can only be redeemed with proof of identification. Paperless tickets are meant to curb scalping—a practice that legislators contend is bad for fans. Lawmakers across the nation have tried different means to undercut scalping, from banning the sale of tickets at a price above face value to prohibiting the use of software that scalpers often employ to amass large amounts of tickets. Outfits like Stubhub oppose efforts to stop ticket transfers, arguing that concert tickets are property until the ticket holder enters the concert venue. At that time, the tickets become revocable licenses. Primary sellers like Live Nation argue that tickets are revocable licenses and nothing more.

The Wall Street Journal recently published an interesting article that considers whether concert tickets are property. The philosophical question has practical implications, as California lawmakers are considering whether to ban paperless tickets, which can only be redeemed with proof of identification. Paperless tickets are meant to curb scalping—a practice that legislators contend is bad for fans. Lawmakers across the nation have tried different means to undercut scalping, from banning the sale of tickets at a price above face value to prohibiting the use of software that scalpers often employ to amass large amounts of tickets. Outfits like Stubhub oppose efforts to stop ticket transfers, arguing that concert tickets are property until the ticket holder enters the concert venue. At that time, the tickets become revocable licenses. Primary sellers like Live Nation argue that tickets are revocable licenses and nothing more.

True, tickets are generally considered licenses— a very limited property right. That is, if property rights are considered a “bundle of sticks,” a license consists of a very small bundle. Use of a ticket entails use of another’s property. In issuing an individual a ticket, the property owner issues that person a license to use his property for a specific purpose. Under property law, licenses are generally non-assignable and revocable for any reason. This lends support for the validity of laws or vendor-instituted policies that limit ticket holders’ ability to transfer their tickets. It seems clear that tickets are a form of property, but the question is, how far does one’s property interest in tickets extend?

Although not determinative of this question, the alienability of property enables the efficient allocation of resources. A paper published last year in Cato’s Regulation magazine supports the notion that allowing scalping to thrive may be beneficial to all parties—scalpers, die-hard fans, and “toe-tappers” alike. It describes Congress’ efforts to enact the Better Oversight of Secondary Sales and Accountability in Concert Ticketing—or, the BOSS Act (yes, that’s a legislative Bruce Springstein reference). The BOSS Act would have prohibited those who sell more than 25 tickets per year from buying tickets within the first 48 hours of sale.

The authors suggest that, contrary to legislators’ and Live Nation’s suggestion, the evolution of secondary markets has meant that ticket scalping now provides better outcomes for consumers. What was the catalyst for this evolution? The spectacular power of the internet, of course. Thanks to sites like Stubhub and Seatgeek, consumers now have better access to information and the ability to easily compare prices. In other words, the internet has made secondary markets for concert tickets more competitive. The phenomenon is akin to the rise of Expedia, Travelocity, and Kayak, which allow travelers to easily compare flight prices. Armed with more information, fans are able to get better deals. The corollary is that ticket holders who may not have thought of selling now have better access to the value of their tickets, and even die-hard fans may now be persuaded to sell. The implications for the BOSS Act are that while “the BOSS Act would have changed who first got their hands on tickets, it might not [have] affect[ed] who end[ed] up with them.” That is, while dealers may not have been able to buy and resell tickets, die-hard fans may have done the same if the price was right on the secondary market.

The authors go on to show that private efforts have done much to curb ticket scalping, and leave tickets close to the stage in the hands of die-hard fans while allocating the remaining tickets to the “foot-tappers” who would rather sit in the back. (foot-tappers being those who are willing to pay more for better seats, but don’t provide the same spill-over benefits of contagious enrapture with the BOSS). Springstein, for example, made tickets in the front paperless; die-hards are much more willing to purchase paperless tickets, as those with slippery hands prefer transferability. Further, the creation of the “pit” keeps those foot-tappers at bay. Finally, laws that prohibit bots are very difficult to enforce, but Ticketmaster has endeavored to hamper bots by developing increasingly complex software.

While the question of the extent to which my Maroon 5 tickets are property remains philosophical, one thing is clear: secondary markets have ameliorated the harms allegedly caused by scalpers. As the authors conclude, “Lift your hands and praise markets!”